Architectural Refinements and Features

It must be noted that late 17th and early 18th century construction of houses in Annapolis Royal was of a rural style, as opposed to city homes in, say, New England. Such buildings would normally be one and a half stories, and would be modest both on the outside and the inside.

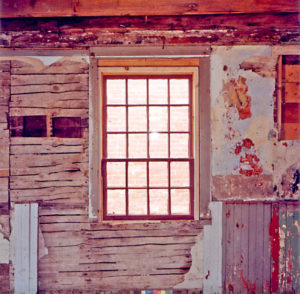

The rough to smooth progression of architectural refinements to the floors, walls, doors, and ceilings of houses can be seen throughout the Sinclair Inn. These changes are the customary progression for most buildings over the past 300 years, reflecting technological changes in styles and materials, as well as the personal preferences and economic prosperity of owners.

Structure

Foundations were usually of fieldstone, and of dry, or clay-mortared construction. In the case of the Soullard House, there was no foundation, and the sill plates were set up on the bare ground. The Skene House was moved and set on an existing foundation.

Large handhewn beams were shaped with a broadaxe, and set into the rock foundations. Wall frames of handhewn stud timbers were strengthened with diagonal timbers of a similar nature as the studs. Mortice and tenon joints and rough wooden pins were used to join the corners. These joints would be cut with augurs, chisel and mallet.

Rafters, plates (horizontal timbers at the top of the wall on which the rafters rested) and joists were handhewn, sometimes only minimally.

Exterior Finish

Once the studs were in place, underboarding, which only became common in the latter part of the 1600s, and which consisted of large sawn planks up to 21 inches in width, was applied to the exterior of the building. Clapboards, which were the typical final finish for the exterior wall, would then be applied to the underboarding. Handmade nails would be used to attach both the underboarding and the clapboards to the structure.

Interior Finish

The Soullard House used no wall filling and relied on underboarding and clapboard. The Skene House, however, and several other Annapolis Royal houses, relied on wattle and daub, a mixture of clay and marsh grasses supported by horizontal staves, as a wall filler.

Various authorities have concluded that the Sinclair Inn (and other early buildings in Annapolis Royal) owes much of its origin to New England concepts. This is particularly evident in the underboarding that was applied to the exterior of the house frame prior to the daub and wattle being installed in the wall cavities. The daub and wattle would be smoothed as much as possible, and in some homes may have provided the final interior finish. A thin layer of clay mixture may have then been applied to the walls.

Paint or wallpaper was traditionally applied to the upper portion of interior walls. By the 1730s, wallpapering had become quite common and was fairly widespread in New England. It wasn’t until after the 1760s, however, that the first papers were commercially produced. By the 1840s, there were wallpaper shops supplying this rising decorating trend. In this period, scenic papers were popular, as interior decoration continued to follow contemporary styles.

Plaster and Lath and Later Developments

Plaster and lath became the most effective way of sealing the house from cold air, and also for providing an attractive finish. Riven lath (the earliest type of lath, which lasted until the late 1700s) was applied in a horizontal fashion to the wall studs with small hand made nails, and the plaster was applied to the laths.

Initially, plaster and lath were attached to the walls only, while ceilings were left open and were white-washed. By the early 1700s, ceilings were being plastered. Plaster walls and ceilings continued to be the norm, well into the 20th century.

The development of new technologies allowed further changes to the ceilings here in the Sinclair Inn. Over the years, plaster ceilings had become cracked and patched and were no longer as attractive as they had once been. The wealthy had always been able to afford beautifully moulded and patterned plaster ceilings, a process that was beyond the means of most people.

But, by the beginning of the 1900s, the availability of thin stamped patterned metal sheets or tin ceilings, (for sale in the local general store in many designs) allowed many people to cover older plaster ceilings and create more sophisticated interiors.

Wainscoting

As plaster walls became common, additional decoration of a room saw wainscoting applied on the lower portion of the wall, especially in the parlor. The first wainscoting was of horizontal broad pine boards on exterior walls and was capped with a chair rail. On interior walls, it ran vertically from floor to ceiling, where it formed a thin partition. It is likely that wainscoting was unpainted until about 1700.

As time went on, wainscoting became vertical pieces of board or raised panelling to the level of the chair rail, with plaster walls above, on all walls. By the latter part of the 1800s, wainscotting was commonly thin pine boards which were often decorated by using graining techniques. This type of refinement slowly moved from the parlor to other rooms.

Stairway

The earliest stairway was enclosed by vertical wainscoting from floor to ceiling, which then developed into a more open construction with a handrail and balusters. The diagonal treads at the bottom of the stairway would be framed into a large, but simple, newel post that might reach from floor to ceiling. The sturdy newel post soon was shortened, topped with a round knob, and balustors were lathe-turned.

Doors

Early exterior and interior doors were essentially of the same style – vertical boards with horizontal supporting battens on one side. Exterior doors were much thicker and heavier, sometimes having two thicknesses of board, and carried by strap hinges. Interior doors were much lighter with H and HL hinges being common. Both these types of hinges had largely disappeared by 1800.

Joined and paneled doors were introduced about 1700. Mortice and tenon joints were used in assembling this refined style of door. The vertical members of the door were called stiles and the horizontal members were called rails. The panels, initially four per door, were fitted within in these pieces, and “float” there to allow for expansion and contraction. In the early stages of joined doors, the primary face had the flat side of the panel, and the secondary side had the feathered edge. Molding began to be attached to the inside edges of the stiles and rails, and was often on both sides of the door. Sometimes, though, only one side had molding.

By 1800, Georgian and Federal doors with six panels became standard. By 1830, Greek revival style moved to four or five panels. And by the end of the 1800s, the five-cross panel door was developed, enduring for a full century. As its name implies, the door had five panels of equal size arranged one above the other.

In the early twentieth century the introduction of plywood revolutionized the manufacture of doors. Three ply panels became far more common than panels of solid wood. One panel and two panel doors often had face veneers of birch or other hardwoods and usually had stiles and rails of glued softwood cores, veneered in hardwood. In the early decades of the twentieth century the “miracle” door was highly popular. It was inexpensive, usually had stiles and rails of pine, and within this framework was an inner frame that held a single plywood panel.

Fanlights

The fanlight was, traditionally, a semi-circular window over the front entry way door. The window was fretted with wooden spokes as glazing bars. It admitted light to an otherwise dark hallway. Fanlights were typically evident in the Georgian period, and as time progressed they became more decorative and more elliptical in shape. They could be compared to the less graceful transom window over the door. Later, fanlights were also used over windows. The Annapolis Heritage Society’s logo is based on the fanlight window.